By John Lienhard

Today, Spiders and STEM education. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Here’s a fine old book. It’s Arabella Buckley’s "Life and Her Children." Buckley knew the great biologists of her day — Darwin, Lyell, and more. She worked for Lyell until he died. Then she began writing science books for young people. Today we talk about STEM education — Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math. Well, this was STEM back in the 19th Century. So, let’s open her book:

She begins by asking us to look at the family bond that unites all living things. She wants us to see how we’re all interconnected. The deeply religious Buckley revels in the miracle of evolution. She describes our wonderfully evolved biosphere.

Let’s look at her chapter on “Snare Weavers.” Mostly, that means spiders. Of course, spiders make many of us cringe! But Buckley knew that children haven’t yet learned to be frightened. They can still see a spider for what it really is — a creature of tenacity and amazing skill. I think there’s something here to bear in mind as we weigh our own STEM tactics.

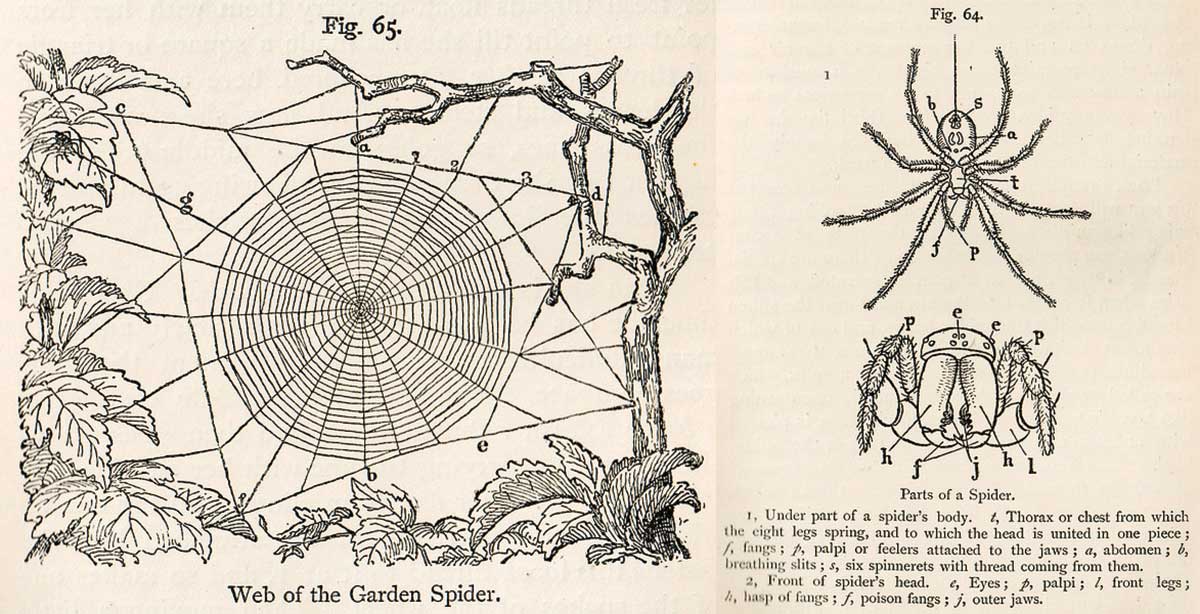

Buckley begins with a garden spider’s body — its jaws, torso, eight legs, and more. Its six spinnerets are fascinating. She tells how each puts out a different filament: Strong structural threads anchor the web. Then radial spokes. Elastic threads then circle the spokes. (They’re the ones that carry tiny adhesive blobs to snare insects.) We learn how spiders capture, then consume, their prey.

It’s all so wonderfully complete. Still ... more recent research has shown just how strong spider silk is. To break it, takes several times the yield stress of common steel. But, unlike steel, it easily deforms. Then it creeps back to its original shape. That way, insects can’t trampoline off a thread once they’ve landed on it.

I’m really surprised she could already tell us that each spider thread is a structure — not a single thread of material. Each spinneret puts out hundreds of incredibly small threads. They give the visible thread its underlying structure.

Buckley finishes by saying, “Thus the 8-legged insects ... make good their right to live ... If we could watch them all in their daily labour, we should find them quite as active and industrious as [we ourselves] ... struggling far more bravely against the thousand dangers and privations which threaten them every moment ... “

And so, Arabella Buckley has used this once maligned creature to capture the young imagination. She teases young people to ask still more questions. Today, we wonder how to make STEM education work. Well, here’s an idea. Let’s not be afraid to engage children with slightly scary themes. But frame them so they trigger curiosity. I think you’ll agree. If we can lay aside our own fears, then nature’s complexities have so much to teach us all — young and old alike.

I’m John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we’re interested in the way inventive minds work.

The Engines of Our Ingenuity is a nationally recognized radio program authored and voiced by John Lienhard, professor emeritus of mechanical engineering and history at the University of Houston and a member of the National Academy of Engineering. The program first aired in 1988, and since then more than 3,000 episodes have been broadcast. For more information about the program, visit engines.egr.uh.edu.