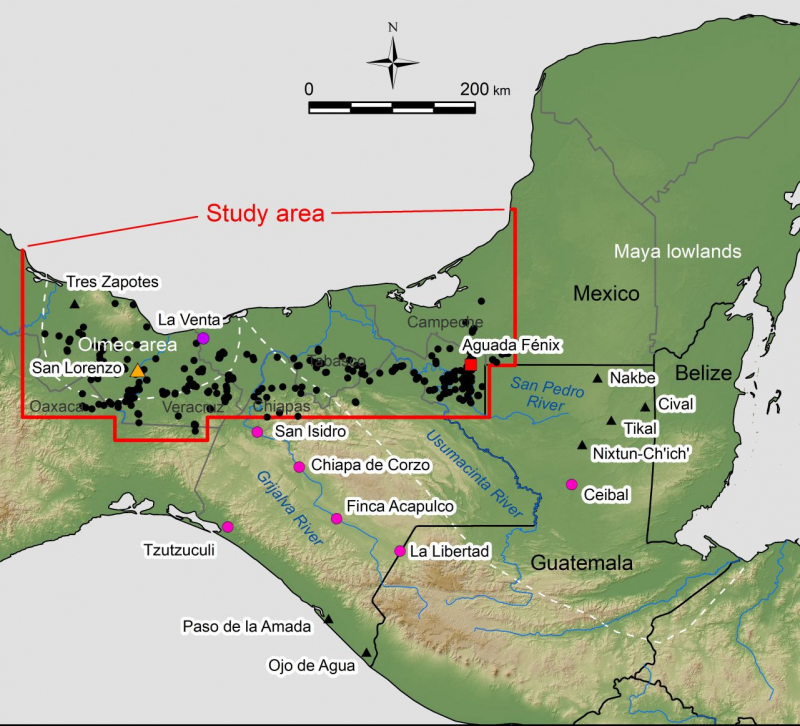

Through the analysis of airborne laser mapping (lidar), an international team of researchers – including several from the Cullen College of Engineering at the University of Houston – identified 478 ceremonial centers in the Mexican states of Tabasco and Veracruz.

Most of those sites likely date to 1100 to 400 B.C., several centuries before the Classic period (A.D. 250 to 950) or the heyday of Maya civilization. Their discoveries transform scholars’ understanding of the origins of Mesoamerican civilizations, particularly the relation between Olmec and Maya cultures.

The research is featured in an article in Nature Human Behavior, initially published on Oct. 25. Juan Carlos Fernandez-Diaz, Ph.D., of the National Science Foundation (NSF) National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping (NCALM) at the University of Houston, and co-author in this study, led UH/NCALM participation in this research, which included other UH faculty and staff. Other researchers are from the University of Arizona.

When asked what attracted him to this research, Fernandez-Diaz said, “As an engineer I constantly admire the efforts ancient cultures put toward creating massive infrastructure projects, either to represent their vision of the cosmos, like we find in this study, or to modify the landscape and environment to their advantage. There are many lessons in conservation and resiliency we could re-learn from studying ancient cultures; and which we can the apply to our current challenges.”

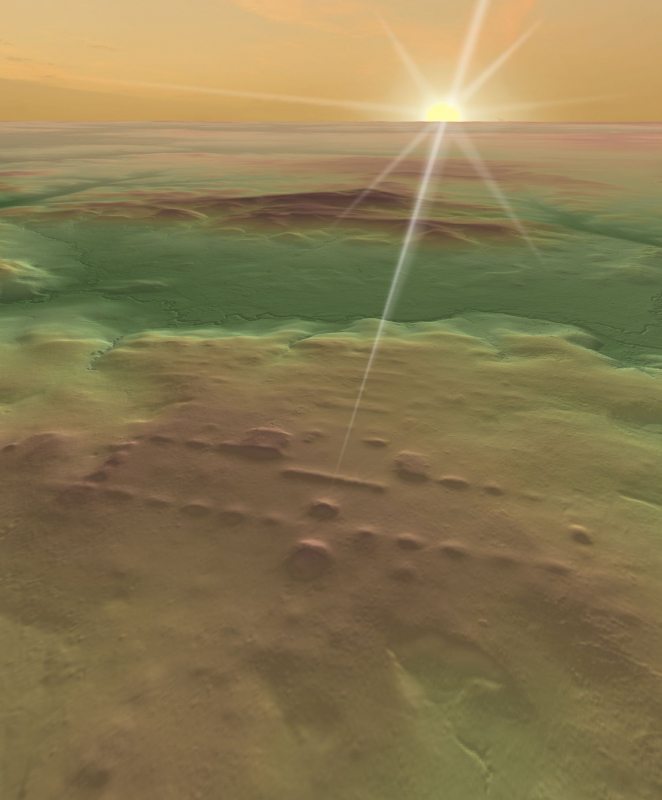

Lidar can map 3-dimensional forms of the ground and archaeological sites by penetrating vegetation. This study used publicly available lidar data obtained by the Mexican governmental organization Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI) and high density lidar data collected by NCALM. It covered an area of 85,000 km2 (equivalent to Ireland), representing the largest archaeological lidar study in Mesoamerica.

UH/NCALM conducted a high density airborne lidar survey of more than 800 km2 in the Mexican states of Tabasco and Campeche. From this survey high definition images were produced of archeological features, which aided in the interpretation of the lower definition images derived from the older lidar data. Fernandez-Diaz reworked previously collected lidar by NASA and INEGI [lidar], particularly INEGI lidar for the archaeological site of San Lorenzo. The reprocessed image of San Lorenzo revealed key architectural features and layout, which are interpreted in this study as a blueprint for the development of later sites in the region.

These complexes shared highly standardized formats, including rectangular plazas demarcated by lines of low mounds. These rectangular forms measured up to 1.4 kilometers (0.87 miles) in length, and the east-west axes of some complexes were oriented to the directions of sunrise on specific dates. These centers were probably the earliest material expressions of basic concepts of Mesoamerican calendars.

The largest of those rectangular complexes, Aguada Fénix, is found in the western Maya lowlands. It was previously reported in Nature (Inomata et al. 2020. Monumental architecture at Aguada Fénix and the rise of Maya civilization) and was first identified in lidar data collected by NCALM in 2017. The present study shows that similar ceremonial complexes spread in a broad area, including the Olmec region and the western Maya lowlands.

The study also suggests that the prototype of those standardized formats was developed at the earlier Olmec center of San Lorenzo between 1400 and 1000 B.C. Through the analysis of lidar data of San Lorenzo, the authors detected a previously unrecognized rectangular form.

San Lorenzo had hierarchical organization, as shown by colossal head sculptures probably depicting rulers. In contrast, the builders of the standardized sites found in this study probably did not have marked social inequality. They appear to have maintained certain levels of mobility, living in ephemeral houses. The enormous constructions made by those no-hierarchical groups force researchers to rethink how early civilizations developed.

These findings show the importance of the legacies of San Lorenzo and the innovations made by later groups. Standardized complexes in this area declined after 400 B.C., but some of their elements were adopted by later Maya centers, providing an important basis for Maya civilization.

Article compiled by Takeshi Inomata, at the University of Arizona, with editing from Stephen Greenwell, at the Cullen College of Engineering at the University of Houston. For more information about this story or to arrange interviews, please contact:

- Takeshi Inomata (University of Arizona) - inomata [at] arizona.edu (inomata[at]arizona[dot]edu), +1-520-408-1064

- Stephen Greenwell (Cullen College of Engineering at the University of Houston) - sjgreen2 [at] central.uh.edu (sjgreen2[at]central[dot]uh[dot]edu), +1-713-743-4094