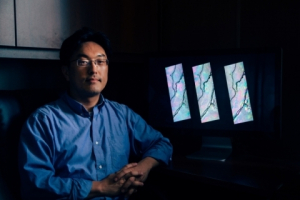

If it has to do with water, you can bet Assistant Civil and Environmental Engineering Professor Hyongki Lee has an appetite whet for it. Fresh off the success of helping Pakistani officials manage water resources, he’s at it again, now selected by NASA to manage water for Indochina.

For Lee, it’s an issue of fairness.

“Although essential for life, water resources are not fairly distributed among countries according to needs,” Lee said. Especially, he added, in the Lower Mekong region where several countries share water resources. “We need to help them build a sustainable system for water management.”

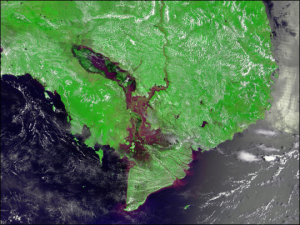

So to shore up water down below, Lee and company take data from high above, gathered by NASA. They then analyze and interpret it to see what impact it has on water systems. With NASA research funds behind him he will build the toolbox to generate satellite-based water management products and applications that can routinely map, warn and enable decision-making on water-related vulnerability issues in low-lying deltas of Indochina.

Lee is the principle investigator (PI) on the project called “Building Lasting Capacity for Water Management in Vulnerable Deltas of Indochina.” His co-investigator is Faisal Hossain of the University of Washington. The program is one of 16 selected by the NASA SERVIR program for funding and will receive $598,527 over the next three years. Derived from the Spanish word meaning “to serve,” SERVIR “connects space to village” by helping developing countries use information provided by Earth-observing satellites and geospatial technologies to manage climate risks and land use, according to NASA.

But without Lee and his team, it’s likely very few people would understand the information NASA collects. NASA distributes its data in raw binary form with different data fields, basically in formats only a rocket scientist could understand.

“We take the raw data, then we analyze and process it to end up with a final product, which could be river level changes and groundwater storage changes, and even forecasting. We use the satellite data to solve scientific problems,” said Lee.

Think of Lee as an interpreter or a water whisperer. His toolbox creates a system for interpretation that he will train the stakeholder agencies in Indochina to use in their decision making on water policies.

Water everywhere

Water might seem plentiful in the Mekong basin, since the Mekong itself is one of the world’s longest rivers. But as the longest poem by English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge will tell you, “Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to drink.”

Lee isn’t the Ancient Mariner – but he’ll tell you why Coleridge is right. He points to construction of dams higher upstream in countries in the Mekong Basin. While they build dams for more access to water, many of the downstream countries, like Vietnam, may get squeezed with not much rolling downhill.

It’s no small problem considering the Mekong River flows through many countries. For example in Cambodia, residents mostly eat fish and depend on it as their main source of protein.

“But if the upstream country builds a dam, it’s going to block the migration of fish,” said Lee. “That means they have new problems related to their own food security.” Lee said increasing capacity in the use of NASA’s satellite data that can provide complementary hydrologic variables with unprecedented accuracy is urgently needed.

The low-lying deltas are also vulnerable to water availability due to dense population and extensive irrigation. That makes groundwater the go-to supply to supplement surface water stocks for irrigation and domestic use. But like a precarious house of cards, over-exploitation of groundwater has led to land subsidence and increased the risk of flood. When you throw in climate change and the inability of other riverside countries to manage water resources, you have the perfect storm.

Making it last

Lee is keen on institutionalizing the project, so that it is sustainable and can be utilized by end users after the project is completed. In fact, his biggest goal is to walk away.

“SERVIR has different application readiness levels. Our goal is to reach the highest level, which means our tools have been implemented by the stakeholder agencies for their decision making, and they do not rely on us after the project ends,” said Lee.

They may not rely on him after he has taught them how to interpret the data, but they will long remember his work in making information understandable and water accessible to those who need it most.