Using data collected from twin NASA satellites, a UH engineering professor is helping officials from the Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources (PCRWR) to manage the country’s groundwater resources from approximately 300 miles above Earth. NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) mission is collecting data that provides a basin-wide snapshot of water resources in the Indus Basin Irrigation System for the first time in history.

Hyongki Lee, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering, was one of the lead trainers on processing and interpreting GRACE data with novel software that he and his colleagues developed. With a NASA grant from the Applied Sciences Program, Lee and his collaborators from the University of Washington and Ohio State University traveled to Pakistan last year to train officials from various water management agencies to use the novel software.

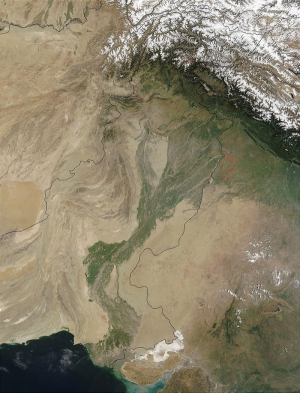

The Indus Basin extends over 449,809 sq.-mi. and stretches into four countries, including Tibet (China), India, Pakistan and Afghanistan. More than 118 million people throughout South Asia depend on the Indus River and its five main tributaries for their livelihoods, according to a 2013 report produced by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) titled “Indus Basin Floods: Mechanisms, Impacts and Management.”

The economic success of countries throughout the Indus region depends primarily on agriculture. In Pakistan, hundreds of miles of farmlands are supported by the world’s largest contiguous irrigation system, the Indus Basin Irrigation System. Throughout the Indus region, groundwater accounts for over 60 percent of the surface water supply. If managed effectively, the waters of the Indus Basin could sustain the lives of the millions of people who live along its banks.

Although groundwater management is a top priority for countries in the Indus region, government officials and policymakers had no way of monitoring total groundwater supplies. Until now, policymakers and stakeholder agencies in Pakistan have relied on traditional methods of water resource management, which included a patchwork of local and provincial plans without any mainstream, basin-wide approach to conserving groundwater supplies.

Moreover, no holistic data existed to inform basin-wide decision-making on groundwater management. Instead, researchers collected data on water levels by hand, which is tedious, time-consuming and subject to human error. Consequently, fundamental questions remained regarding how best to manage groundwater resources: How much groundwater exists? How does the groundwater storage change temporally? How is the groundwater being depleted and replenished? For the first time, officials were given answers to these questions by using the software to interpret the GRACE data.

The GRACE mission satellites are circling the Earth in the same orbit, one trailing roughly 137 miles behind the other. Slight changes in the gravitational pull on the satellites can cause one to pull away from the other, increasing the distance between the two satellites. Researchers can monitor changes in the distance between the two satellites down to one micron – about 1/50th the width of a human hair – to detect tiny fluctuations in the gravitational field. The changes in gravity are associated with shifts in mass, such as the movement of water on Earth. By tracking changes in the gravitational pull on the satellites, researchers can now map the movement of water on Earth and gain invaluable information to inform decision-making on water management.

Although this project focused specifically on managing groundwater resources throughout the Indus basin, Lee noted that this type of research can be applied to a variety of projects in order to better understand the environment and impact peoples’ lives for the better.

In another project that began a few years ago, Lee composed computer algorithms to translate NASA’s Jason-2 satellite altimetry data on river water levels throughout the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna Basin into robust flood prediction data sets. Last year, the Bangladesh Flood Forecasting Warning Center officially adopted the system to accurately predict floods up to eight days before they occurred, providing those living in the region with an additional five days for preparation.

Lee and his collaborators will also travel to Vietnam, Bhutan and Nepal to train officials to operate the software toolkits and to solicit feedback to further customize the toolkits for the specific needs of each country.

“NASA encourages engineers to find novel ways to use satellite data for positive impacts on the Earth, and I specialize in that area of research,” Lee said. “The software we develop will strengthen the ability of governments and other stakeholders to use NASA’s satellite data to respond to natural disasters.”

Read more about this story here.