When young Eddy Goldfarb was 6 years old, a man who would change his life visited the family house for dinner. This man had an unusual occupation, and the more he shared, the more he fascinated the precocious youngster from Chicago.

At that point, Goldfarb had already exhibited the distinctive creative streak that would shape his entire life.

“I bothered my mother with ideas when I was young, but I would not take the quarter she would offer me to stop talking,” Goldfarb, now 102, says with a laugh. “I was always creative and inventive; I think I was lucky in that way.”

It might be kismet, then, that a man with a most creative occupation stepped into his life that fateful day nearly a century ago. The man was an inventor, and as he explained his profession, Goldfarb hung on his every word. He knew right then that he, too, wanted to be an inventor — specifically an independent inventor.

“Companies have wonderful R&D departments and wonderful inventors, but I knew I wanted to be independent,” he says.

Goldfarb fulfilled that dream ... and many others. In fact, the 102-year-old is still creating thanks to a 3D printer and a penchant for writing.

But remember: At the time of his fateful meeting with the inventor, Goldfarb was just 6 years old. The year was 1927, and in the decades between then and now, he would grow up to become one of the most revered toy inventors of all time. But first, he would become many other things — including a student at the University of Houston during one of the most challenging periods in U.S. history.

EDDY'S MILITARY CAREER SETS SAIL AT UH

On Dec. 7, 1941, Goldfarb heard a special news bulletin crackling through the radio in his apartment. Pearl Harbor had been the victim of a surprise attack, and it was clear the United States was now officially involved in World War II. Eager to serve his country, Goldfarb volunteered for the Navy. His ultimate destination was the Pacific, but first, he moved into the Navy’s barracks at the University of Houston, where he studied electrical engineering and entered an in-depth program for radar technicians.

“We marched from our barracks to the classroom every day,” he recalls. It may not sound like the right fit for a creative spirit, but Goldfarb relished everything about the experience.

The University was still open to the general public, so he and his fellow naval trainees met and befriended plenty of students, even if they were far removed from life in the barracks. He fell in love with the campus community and the community off campus, too. In one instance, a family near campus provided a perfect example of Texas hospitality.

“My mother wanted to come visit me; she was so worried, and I wanted her close,” he says.

His mother couldn’t stay with him in the barracks, though, and Goldfarb figured he’d have to look far and wide until he found a family that would welcome a visitor.

“So, I went to a few houses next to the University and asked them if they could rent out a room for a few days, and it only took me three or four,” he says. “This wonderful family agreed to take my mother in.”

When he wasn’t making friends — sometimes in unexpected places — Goldfarb was immersed in his studies. It may have been a 12-month program, but he says the knowledge they imparted was enough to fill a multiyear curriculum. This rigor had a clear purpose and was both exciting and daunting: The Chicagoan and his contemporaries were learning nascent technology that would fuel their efforts on the battlefield. Or to be more specific, at sea.

After his time at UH, Goldfarb decamped to a secretive radio lab at “Treasure Island” in San Francisco. If you scored high enough on the assessment tests at this secretive, final program, you could choose your posting in the armed forces. That’s how Goldfarb, an excellent student, went to work on submarines with two of his friends.

“We could pick up submarines as far away as the horizon,” he says, still marveling at what he and his team could achieve.

His seven patrols took him near Midway, to Guam, Palau and beyond, and in total, his submarine — the USS Batfish — is credited with sinking nine Japanese ships, including three within a four-day span. These engagements came at a cost; one of Goldfarb’s closest friends died in combat. No matter how much time has passed, those years are tinged with pain and hard-won lessons.

“It was a horrible time, but I made some friends for life, and I realized what was really important,” he recalls.

Those years of service taught him to not sweat the small things and, when possible, find a silver lining.

“I was lucky enough to make it, come home, meet my wife and have a family,” he says, “So, I appreciated that very much.”

EIGHT DECADES OF INVENTION

During his submarine duty, Goldfarb used his downtime to fill notebooks with ideas and sketches, including dreams of self-landing helicopters. His years in school had fostered a love of physics and engineering, but he still held onto the aspiration he’d had since age 6.

“I enjoyed working with children, so at one time I had to choose: ‘Should I go into physics, or should I stay an inventor?’” he says. “I liked the idea of working with toys because toys bring families together. If you invent a game and they sell a million of ‘em, you know a million families. I think that’s very important.”

That’s not to say his toy career was always smooth sailing — quite the opposite. After returning from the war at the end of 1945, he became familiar with the habitual rejection that’s a staple of every creative career. He had plenty of ideas, but each one was met with a “no” by the manufacturers he pitched.

Around that time, he met Anita, his future wife. The pair were married just nine months after a chance encounter at a veterans’ dance, and to save money, Goldfarb moved into Anita’s bedroom in her parents’ apartment. Both families had reservations about the ambitious inventor’s toy aspirations, but his big break was around the corner — and it was in the form of teeth.

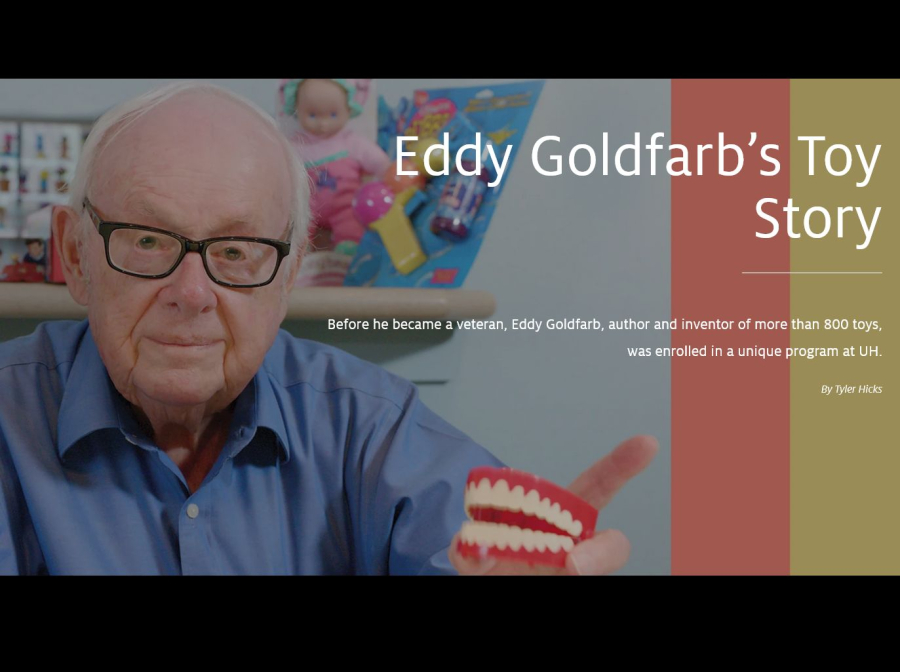

You’ve undoubtedly seen the toy that was originally called “Yakity-Yak Talking Teeth”; it’s been in “The Office,” “The Goonies,” “A Christmas Story” and possibly even your home. The iconic chattering teeth toy was originally made by Goldfarb, sitting alone at the kitchen table, using a set of false teeth, some casting and a repurposed motor. That invention ultimately landed him a spot at the 1949 Toy Show in New York, and he was off to the races, using one opportunity after another to gradually build a legendary career.

There were still setbacks, of course; pursuing an independent career is never easy. Yet Goldfarb’s combination of grit and optimism laid the foundation for a storied, decades-long run that includes toys and games like the bubble gun, Battling Tops, KerPlunk, Vac-U-Form and many, many more. The initial sale and success of his chattering teeth creation taught him he should always license his creations rather than sell them outright. And one of his licensing deals has a rather unusual origin story.

During a rough patch early in his career, he booked a one-way ticket to a Chicago toy show to which he was — technically speaking — not invited. When he couldn’t get in through the front, Goldfarb checked every door until finding one that opened. He eventually apologized for his persistence, but Ideal Toy Company saw something they liked — and they liked his toys even more. That same company would license more than 50 of his 800-plus inventions which, in turn, paved the way for his work with Mattel.

This is one of the central lessons Goldfarb would like to share with aspiring creators, businesspeople and entrepreneurs of every kind: Don’t give up and use one success to get to another.

“There is always rejection and disappointment, so my advice to anyone is to always do as much research as you can and keep going,” he says.

It also helps to surround yourself with talented and passionate people. Over the years, he has worked with respected toy creators like Del Everitt, René Soriano and his son, Martin Goldfarb, who has been his collaborator for the past three decades.

“I started alone, but I ended up with 39 people on my staff: artists, engineers, what have you. I did not do it alone.”

Someone would bring an idea to the table, and the team would kick it around, seeing what would stick, what didn’t and how they could toy around with it (pun intended) until it became a viable model.

“Every item we ever invented, I knew it was going to be an amazing item,” he says. “And it wasn’t. Very few were amazing because we came up with so many ideas. I’m still very optimistic, and I’m very lucky to have that trait.”

Now, at an age few people reach and at which even fewer people are still working, Goldfarb is still honing his creative chops.

He uses a 3D printer to make lithophane: transparent materials typically constructed from porcelain. He writes, too. Goldfarb recently published a book of 101 100-word stories, some of which date back to a story contest he entered as a teenager. That story, “The Perfect Twenty Dollar Bill,” is about a man who thinks he makes an immaculate counterfeit bill — until he gets caught buying a cheeseburger.

“How did you know?” the man asks the boy who calls the police.

As it turns out, the man had indeed made a perfect bill, but it was a perfect copy of a counterfeit bill.

“I didn’t win the contest,” Goldfarb recalls with a chuckle, his hallmark optimism shining through. “But I kept writing.”

To see a gallery of some of Goldfarb's inventions, click here!