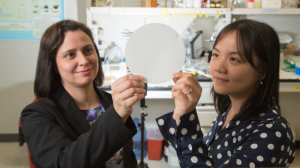

When it comes to clean water, Yandi Hu and Debora Rodrigues have a thirst for it. Hu, UH assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering, works with Flint, Michigan on their water crisis and conducts research on reducing lead release in water lines. Rodrigues, UH associate professor of civil and environmental engineering, helps improve global access to clean water with a nano-sized technology that can weed out metals and microorganisms from drinking sources. Now they’ve teamed up and received a grant for $184,000 from the Qatar National Research Fund to change the world of water purification by making it more efficient and less expensive.

“This work can be very transformative,” said Hu of the joint project called “Mechanistic study of using polymer-modified graphene oxide nanocomposites for controlling CaSO4 scaling and biofouling on reverse osmosis membrane.”

The scope of the problem

To understand their work, you have to understand the scope of the problem. Saltwater comprises 97 percent of the earth’s water supply. To convert that seawater into drinkable, or potable water, it undergoes the desalination process, which includes reverse osmosis, in which minerals and salts are removed by passing through filter screens, called membranes.

“In the United States, 70 percent of reverse osmosis desalination plants are affected by mineral scaling and severe membrane biofouling from a buildup of bacteria,” said Rodrigues.

“The minerals clog the pores and bacteria can grow on the membrane surfaces,” added Hu. “When this clogging happens, high pressure is required to push the water through the membranes and that costs more energy.”

More money, too. In California, at the Water Factory 21 desalination plant, at least $728,000 is spent on membrane cleaning. That’s 30 percent of their operating costs. The clogging is not only expensive to clean, it seriously reduces membrane performance and lifetime.

Rodrigues and Hu have a better way to eliminate mineral scaling and biofouling.

They’re going to modify the surface of the filter by using a polymer-modified graphene oxide nanocomposite to coat the membranes. They predict the new coating they are developing will prevent the buildup.

They have good reason to be positive.

Rodrigues had already determined that graphene oxide (GO) can kill bacteria and prevent biofouling. In Hu’s lab they’ve been working on the concept that polymers could prevent mineral scaling. Now they’re combining the GO with the polymers to see if they can combat both threats at once.

But the questions abound

Like a blended family, the combination of properties has to be carefully measured. Bacteria may actually degrade polymers, and polymers might actually promote the growth of bacteria by becoming its food.

Problems to be faced by Rodrigues and Hu as they work together to blend their knowledge, talents and expertise to meet the worldwide challenge of keeping the water supply plentiful and healthy.