ME graduate walks in commencement six decades after earning degree

When John Berry Rogers (1950 BSME) attended the University of Houston Cullen College of Engineering things were a lot different. The roads were not paved, buildings on campus lacked air conditioning and men didn’t always have a choice to enlist in the military and go to war.

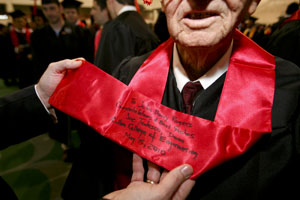

It was a world far different than the one known by most spring graduates that Rogers walked the stage of Hofheinz Pavilion with Saturday. Yet despite the differences, just like them, Rogers was celebrating a milestone. Or, to be more accurate, he was collecting on a privilege war didn’t allow him 60 years ago when his United States Navy unit was called to provide support in the Korean War.

The chance to be recognized for his achievement, in cap and gown while surrounded by family just two weeks before his 91st birthday, was nearly indescribable.

“My education from the University of Houston was something I always treasured,” said Rogers, who still wears his class ring, now quite worn. “To be able to finally recognize my accomplishment, it’s really something special.”

For Rogers, never being handed the piece of paper symbolizing his mechanical engineering degree in person with all his peers was a missed opportunity that had always lingered in his mind. It was a regret he shared with his grandson Toby Hooper as they rooted on Rogers’ alma mater in football at the Armed Forces Bowl game in December.

“We braved the cold to support the team,” Hooper recalled of the Dec. 31 trip Rogers took with Hooper, another grandson and a great-grandson. “It was at that time that he told us the story that he had always wished he could have gone through commencement. I just had to see if I could do something.”

So Hooper began calling and sending e-mails to university staff. Eventually he reached Renia Lusby, events assistant at UH, who took the steps to get approval to make Rogers longtime wish possible. Lusby, who has been coordinating commencement at the university for the last three years, said the effort put forth by Rogers’ family was hard to ignore.

“I hope one day I have grandchildren that care about me like Toby cares about his grandfather,” said Lusby. “As soon as he shared the story of his grandfather, that’s all I needed to hear.”

After receiving the proper blessings from the provost and others above her, Lusby made arrangements for Rogers to join the estimated 262 students collecting degrees in the Cullen College.

With all the details falling in place, Hooper called his grandfather—who was unaware of his efforts—a month prior to spring commencement and shared his quest to give him back the opportunity he had lost so many years ago.

“I wasn’t really expecting it,” Rogers shared from his home in Stephenville, Texas. “To tell you the truth, I got a little teary-eyed at the gesture. It's something I'd always wanted to do, but never had the opportunity.”

The degree had always meant a lot to him. The son of a sharecropper, he was the first in his family to earn a high school diploma, let alone the college degree.

He grew up in rural Erath County, Texas. And after high school he worked on a chicken farm until the Depression-era agency, the Works Progress Administration, offered him the chance to participate in a training program teaching him machine shop operation.

“It really opened doors for me,” Rogers said, noting that after finishing the three-month program at Texas A&M University he started work as a machinist at Reed Roller Bit in Houston. It wasn’t long before the Japanese would attack Pearl Harbor, and four months later, in March of the next year, the cruiser USS Houston would fall to the Japanese.

“When it sunk over 1,000 lives were lost,” Rogers said of the USS Houston. “They were trying to recruit people in the city to replace these men.”

So on May 25, 1942, Rogers was among 1,000 men to step forward and volunteer to replace the Houston crew by enlisting in the Navy during WWII. The entire group, Rogers said, took the Navy oath in a street ceremony in downtown Houston as some 200,000 looked on.

It was the first in a series of sacrifices Rogers would make to earn his college education.

During WWII, he would serve three-and-a-half years on three separate ships in the Pacific as a machinist mate—missing the birth of two of his three children—before being honorably discharged and returning to Houston. But these sacrifices for his country had earned him his first opportunity, at 27 years old, to pursue a college education with the military’s GI Bill.

“UH was a real benefit to veterans,” he said. “They gave us a home and a chance at a degree with the GI Bill.”

Thousands of veterans, just like Rogers, enrolled at UH following the war. Like Rogers, many raised their families in the makeshift quarters they once called Veteran's Village—rows of trailers setup as temporary housing on university grounds.

Though the GI Bill helped fund Rogers’ education, he needed money to support his family, so he went back to his former job at Reed Roller Bit and balanced school, work and family life. Still, despite the cheap rent in Veteran’s Village—just $10 a month—it became difficult for his growing family to get by. Soon, Rogers said, he made the difficult decision to re-enlist in the military as a Navy reservist to supplement his family’s income.

Two years later, Rogers would receive news that would make his knees buckle and change the plans for his approaching graduation celebration.

The Navy had called his reserve unit to active duty. It happened so fast, there wasn’t even time to finish his last two classes. He had to leave three weeks shy of the end of the semester. Like many veterans, his transcript reflects this—showing two grades of Q.

“That’s what they did back then,” he said. “It meant I was successfully passing at the time of termination, so I was able to get my degree.”

He saw his degree for the first time when he returned to Houston after a year and a half on the USS Glendale.

The document, now yellowed and the black jacket dusty and scratched, is more than just paper bound in leather to Rogers and his family. The degree started a tradition for his three daughters, their five children and his 10 great-grandchildren. Through his dedication to the pursuit of higher education each know that no matter what is thrown at you, a college degree will always be worth striving for.

| Graduation By The Numbers |

|---|

*All numbers are estimated. Final numbers are not available until after semester grades, which include final exam scores, have been calculated. |