Since he was a kid, Jose Vazquez (1989 BSCE, 1990 MSCE, 1995 PhD CE) has appreciated the practicality and application of engineering. His father worked in construction, introducing him to engineers and architects, which sparked Vazquez’s interest in both fields.

“It was a toss up between architecture and civil engineering,” says Vazquez, who lives and works in New Orleans. “Civil engineering was the most real engineering I could see. A benefit of having an engineering education is that with engineering you can logically reason most any problem. As compared with the other engineering disciplines, civil engineering, like architecture, can be experienced in everyday life.”

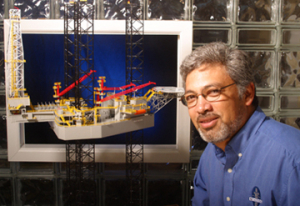

Residents across the nation will feel the effects of Vazquez’s latest project, a deep water liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal using the Soft Berth™ system, developed by Bennett and Associates and Freeport McMoRan Energy LLC, that has been in development for the last year and a half. The system has the potential of affecting heating and cooling systems by stabilizing the supply of natural gas.

“This project is quite challenging in that it involves strong interaction effects in hydrodynamics and structural analyses that have never been done,” Vazquez says. “The deep water LNG terminal is an offshore place where liquefied natural gas carriers will come and unload their cargo as they would in any port, like the one in Lake Charles, LA, but far away from any populated areas. There, the liquid will be processed and the gas stored and distributed. What Soft Berth™ does is allow the vessel to come in and ‘park’ next to this facility.”

Using the Soft Berth™ technology, the LNG carrier can get closer to the terminal due to a more finely calibrated system that will work with the motion of the waves.

“The oscillatory wave loads are so high that it would take a massive structure to keep the vessel from moving,” Vazquez says. “By allowing it to move, the resistance is lowered significantly to as little 10-15 percent. This is comparable to the idea that in a hurricane, trees that bend don’t get broken. Soft Berth™ allows the system to be more flexible and resist the loads by movement or inertia as opposed to stiffness.”

Currently, a scale model is under construction and will be tested in a wave basin in Holland to ensure that the design is adequate. However, the process of this project has not been easy due to its innovative nature.

“One of the first obstacles was convincing ship owners that you could actually hold the vessel near the fixed platform regardless of the direction of the environment,” Vazquez says. “There are other deep water terminals that are comparable, but in other systems the vessels realign themselves or they are protected by long breakwaters, meaning that they can not be in very deep waters. The one we have is affected by weather direction, but it doesn’t have to weathervane.”

Though Vazquez and his team are moving outside of the box in their field, he insists that they are doing so “with proven technology that just hasn’t been put together in this form. This terminal will allow a more steady flow of gas that in the south will translate into air conditioning and in the north, heating,” Vazquez says. “It may not be seen, but it will definitely be felt. It will hopefully put a more even price on gas as well.”

As a student at the University of Houston, it was the professors who enhanced his knowledge of engineering in the real world that influenced Vazquez the most.

“Professor T.C. Hsu was our reinforced concrete design professor, and he started the class with a slide show with many stories of concrete buildings and bridges from all over the world,” Vazquez says. “The class started with a lesson on why you would reinforce concrete, why you need to know how to do that, and why it makes a difference. He was a very good, methodical teacher. My specialty isn’t concrete, but he reinforced how engineering affects people beyond the classroom.”

Vazquez received his bachelor’s degree and graduated Summa Cum Laude in 1989, but he forged ahead and obtained his master’s and Ph.D. in civil engineering, with an emphasis in offshore structures.

“My perception of being an engineering student is different than most because I got three degrees at UH,” Vazquez says. “When I was in the master’s program, I started to see engineers that were working and taking classes in the evenings and late afternoons. This structure in the college of engineering at UH allows students to interact with working engineers. You could ask them if what you were learning was useful and relevant.”

While a graduate student, and a member of the Maritime Systems Engineering faculty in Galveston, Vazquez also served as secretary and vice-chair of the Houston chapter of Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, a division of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, and he encourages students to get involved in similar organizations.

“It’s very important, even more so as a student, to see what’s relevant in the field,” Vazquez says. “By being active in a professional engineering society, students can keep up with what’s truly important.”

Garnering a variety of work experiences, along with a strong knowledge of the fundamentals, are both integral to a successful career, Vazquez says.

“It’s great to have an internship and go back to work for the same company and in the same field because you were good, but it’s better for students, as future engineers, to get different experiences because engineering is so broad that you cannot see everything in four years,” Vazquez says. “Doing so will open your eyes to the possibilities, and you owe it to yourself to see what all is out there.”