By John Lienhard

Today, let’s talk about research and water. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The word research takes a beating. Should we call it research when we just look up information? We academics see research as creating new knowledge. And a huge spur to my own research has been studying water in motion. It’s so complex: How does water and other liquids behave when we handle them, heat them, cool them — hold them up to the light?

Think about spraying liquids: It takes so much energy to create the surface of a liquid droplet. Yet nature makes clouds, white caps, rain, fog. Water drops absorb most of a waterfall’s energy before it hits bottom. I was once kept away from the base of Iceland’s Seljalandsfoss waterfall. Instead of making a big splash, it drove us away with a drenching rain.

That’s why lawn sprinklers use every kind of ingenious means for chopping water into droplets. Another way to create droplets of a liquid is by heating it until it explodes. Turns out, we can heat liquids far beyond their boiling points. Then they explode into fine mists.

The patterns of boiling liquids are so complex. But we need to understand those patterns in real equipment. And that takes serious analysis.

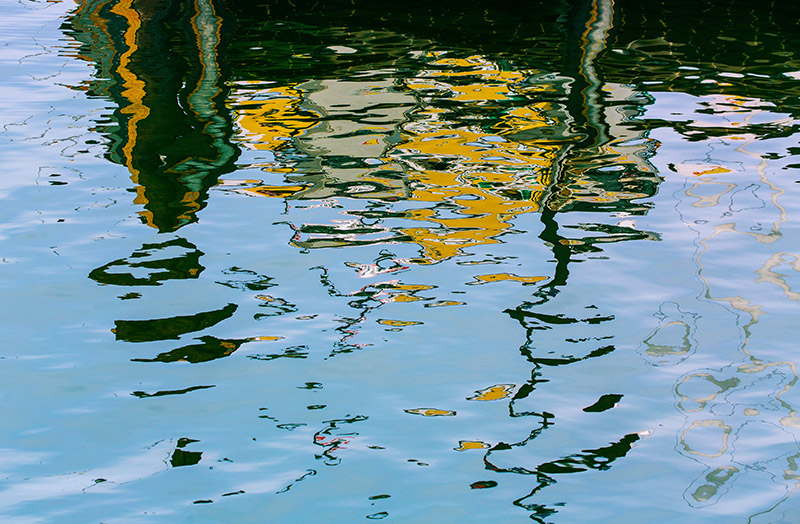

Then there’s color: Water parades in every color of the rain-bow. Well, the rainbow itself is no more than water droplets that refract and reflect sunlight. One 19th century scientist tried to prove that water was really blue in color. He shone white light through a long tube filled with very pure water. The light came out blue. But he didn’t know that water filters out red wavelengths. Blue was all the light that was left.

We now know that water has no color of its own. But, oh, the wonderful colors it refracts! Think about Newton shining light through a prism to get the rainbow spectrum of color. Well, shine white light through a bubbling fountain and we get the same colors, but in strange abstract shapes. Try it sometime. Then there’s rainfall finding its way out of a drainage basin. Turns out you can describe those raindrops with the same math that tells how velocity distributes among air molecules. Follow droplets from leaves to trickles, to rivulets, to streams, and you can learn how flooding occurs at the bottom of the basin.

Or direct a jet of water at a metal disc. A dainty sheet of water then spreads out in the shape of a bell. Or let a small water flow leave a sink faucet. When it hits the bowl it first spreads in a thin, fast-moving sheet. Then it makes a circular jump to a thick slow-moving flow. That’s called a hydraulic jump. People who build dams find ways to trigger that jump in the dam’s spillway to keep the flow from scouring out the riverbed below. So much water research done. So much left to do.

But I now need to say, I’m John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we are interested in the way inventive minds work.

John Lienhard